- the concept of needs, in particular the essential needs of the world's poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

- the idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment's ability to meet present and future needs."

When you think of the world as a system over space, you grow to understand that air pollution from North America affects air quality in Asia, and that pesticides sprayed in Argentina could harm fish stocks off the coast of Australia.

And when you think of the world as a system over time, you start to realize that the decisions our grandparents made about how to farm the land continue to affect agricultural practice today; and the economic policies we endorse today will have an impact on urban poverty when our children are adults.

We also understand that quality of life is a system, too. It's good to be physically healthy, but what if you are poor and don't have access to education? It's good to have a secure income, but what if the air in your part of the world is unclean? And it's good to have freedom of religious expression, but what if you can't feed your family?

The concept of sustainable development is rooted is this sort of systems thinking. It helps us understand ourselves and our world. The problems we face are complex and serious—and we can't address them in the same way we created them. But we can address them.

It's that basic optimism that motivates Darmawangreenfund's staff, associates and board to innovate for a healthy and meaningful future for this planet and its inhabitants.

Sustainable development is a pattern of resource use that aims to meet human needs while preserving the environment so that these needs can be met not only in the present, but also for future generations. The term was used by the Brundtland Commission which coined what has become the most often-quoted definition of sustainable development as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."[1][2]

Sustainable development ties together concern for the carrying capacity of natural systems with the social challenges facing humanity. As early as the 1970s "sustainability" was employed to describe an economy "in equilibrium with basic ecological support systems."[3] Ecologists have pointed to The Limits to Growth,[citation needed] and presented the alternative of a "steady state economy"[4] in order to address environmental concerns.

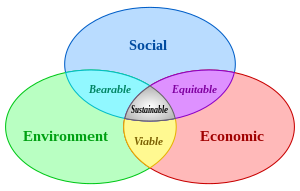

The field of sustainable development can be conceptually broken into three constituent parts: environmental sustainability, economic sustainability and sociopolitical sustainability.

Scope and definitions

A representation of sustainability showing how both economy and society are constrained by environmental limits (2003)[5]

The natural resource of wind powers these 5MW wind turbines on this wind farm 28 km off the coast of Belgium.

In 1987, the United Nations released the Brundtland Report, which defines sustainable development as 'development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.'[8]

The United Nations 2005 World Summit Outcome Document refers to the "interdependent and mutually reinforcing pillars" of sustainable development as economic development, social development, and environmental protection.[9]

Indigenous peoples have argued, through various international forums such as the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and the Convention on Biological Diversity, that there are four pillars of sustainable development, the fourth being cultural. The Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity (UNESCO, 2001) further elaborates the concept by stating that "...cultural diversity is as necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for nature”; it becomes “one of the roots of development understood not simply in terms of economic growth, but also as a means to achieve a more satisfactory intellectual, emotional, moral and spiritual existence". In this vision, cultural diversity is the fourth policy area of sustainable development.

Economic Sustainability: Agenda 21 clearly identified information, integration, and participation as key building blocks to help countries achieve development that recognises these interdependent pillars. It emphasises that in sustainable development everyone is a user and provider of information. It stresses the need to change from old sector-centred ways of doing business to new approaches that involve cross-sectoral co-ordination and the integration of environmental and social concerns into all development processes. Furthermore, Agenda 21 emphasises that broad public participation in decision making is a fundamental prerequisite for achieving sustainable development.[10]

According to Hasna Vancock, sustainability is a process which tells of a development of all aspects of human life affecting sustenance. It means resolving the conflict between the various competing goals, and involves the simultaneous pursuit of economic prosperity, environmental quality and social equity famously known as three dimensions (triple bottom line) with is the resultant vector being technology, hence it is a continually evolving process; the 'journey' (the process of achieving sustainability) is of course vitally important, but only as a means of getting to the destination (the desired future state). However, the 'destination' of sustainability is not a fixed place in the normal sense that we understand destination. Instead, it is a set of wishful characteristics of a future system.[11]

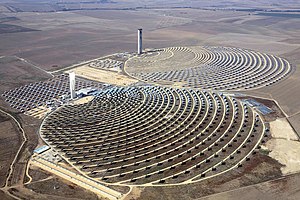

Solar towers utilize the natural resource of the sun, and are a renewable energy source. From left: PS10 and PS20 solar towers.

Some research activities start from this definition to argue that the environment is a combination of nature and culture. The Network of Excellence "Sustainable Development in a Diverse World",[12] sponsored by the European Union, integrates multidisciplinary capacities and interprets cultural diversity as a key element of a new strategy for sustainable development.

Still other researchers view environmental and social challenges as opportunities for development action. This is particularly true in the concept of sustainable enterprise that frames these global needs as opportunities for private enterprise to provide innovative and entrepreneurial solutions. This view is now being taught at many business schools including the Center for Sustainable Global Enterprise at Cornell University and the Erb Institute for Global Sustainable Enterprise at the University of Michigan.

The United Nations Division for Sustainable Development lists the following areas as coming within the scope of sustainable development:[13]

Sustainable development is an eclectic concept, as a wide array of views fall under its umbrella. The concept has included notions of weak sustainability, strong sustainability and deep ecology. Different conceptions also reveal a strong tension between ecocentrism and anthropocentrism. Many definitions and images (Visualizing Sustainability) of sustainable development coexist. Broadly defined, the sustainable development mantra enjoins current generations to take a systems approach to growth and development and to manage natural, produced, and social capital for the welfare of their own and future generations.

During the last ten years, different organizations have tried to measure and monitor the proximity to what they consider sustainability by implementing what has been called sustainability metrics and indices.[14]

Sustainable development is said to set limits on the developing world. While current first world countries polluted significantly during their development, the same countries encourage third world countries to reduce pollution, which sometimes impedes growth. Some consider that the implementation of sustainable development would mean a reversion to pre-modern lifestyles.[15]

Others have criticized the overuse of the term:

- "[The] word sustainable has been used in too many situations today, and ecological sustainability is one of those terms that confuse a lot of people. You hear about sustainable development, sustainable growth, sustainable economies, sustainable societies, sustainable agriculture. Everything is sustainable (Temple, 1992)."[15]

Environmental sustainability

Water is an important natural resource that covers 71% of the Earth's surface. Image is the Earth photographed from Apollo 17.

An "unsustainable situation" occurs when natural capital (the sum total of nature's resources) is used up faster than it can be replenished. Sustainability requires that human activity only uses nature's resources at a rate at which they can be replenished naturally. Inherently the concept of sustainable development is intertwined with the concept of carrying capacity. Theoretically, the long-term result of environmental degradation is the inability to sustain human life. Such degradation on a global scale could imply extinction for humanity.

| Consumption of renewable resources | State of environment | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|

| More than nature's ability to replenish | Environmental degradation | Not sustainable |

| Equal to nature's ability to replenish | Environmental equilibrium | Steady state economy |

| Less than nature's ability to replenish | Environmental renewal | Environmentally sustainable |

The notion of capital in sustainable development

The sustainable development debate is based on the assumption that societies need to manage three types of capital (economic, social, and natural), which may be non-substitutable and whose consumption might be irreversible.[16] Daly (1991),[17] for example, points to the fact that natural capital can not necessarily be substituted by economic capital. While it is possible that we can find ways to replace some natural resources, it is much more unlikely that they will ever be able to replace eco-system services, such as the protection provided by the ozone layer, or the climate stabilizing function of the Amazonian forest. In fact natural capital, social capital and economic capital are often complementarities. A further obstacle to substitutability lies also in the multi-functionality of many natural resources. Forests, for example, not only provide the raw material for paper (which can be substituted quite easily), but they also maintain biodiversity, regulate water flow, and absorb CO2.Another problem of natural and social capital deterioration lies in their partial irreversibility. The loss in biodiversity, for example, is often definite. The same can be true for cultural diversity. For example with globalisation advancing quickly the number of indigenous languages is dropping at alarming rates. Moreover, the depletion of natural and social capital may have non-linear consequences. Consumption of natural and social capital may have no observable impact until a certain threshold is reached. A lake can, for example, absorb nutrients for a long time while actually increasing its productivity. However, once a certain level of algae is reached lack of oxygen causes the lake’s ecosystem to break down suddenly.

Market failure

Before flue gas desulfurization was installed, the air-polluting emissions from this power plant in New Mexico contained excessive amounts of sulfur dioxide.

The business case for sustainable development

The most broadly accepted criterion for corporate sustainability constitutes a firm’s efficient use of natural capital. This eco-efficiency is usually calculated as the economic value added by a firm in relation to its aggregated ecological impact.[19] This idea has been popularised by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) under the following definition: "Eco-efficiency is achieved by the delivery of competitively priced goods and services that satisfy human needs and bring quality of life, while progressively reducing ecological impacts and resource intensity throughout the life-cycle to a level at least in line with the earth’s carrying capacity." (DeSimone and Popoff, 1997: 47)[20]Similar to the eco-efficiency concept but so far less explored is the second criterion for corporate sustainability. Socio-efficiency[21] describes the relation between a firm's value added and its social impact. Whereas, it can be assumed that most corporate impacts on the environment are negative (apart from rare exceptions such as the planting of trees) this is not true for social impacts. These can be either positive (e.g. corporate giving, creation of employment) or negative (e.g. work accidents, mobbing of employees, human rights abuses). Depending on the type of impact socio-efficiency thus either tries to minimize negative social impacts (i.e. accidents per value added) or maximise positive social impacts (i.e. donations per value added) in relation to the value added.

Both eco-efficiency and socio-efficiency are concerned primarily with increasing economic sustainability. In this process they instrumentalize both natural and social capital aiming to benefit from win-win situations. However, as Dyllick and Hockerts[21] point out the business case alone will not be sufficient to realise sustainable development. They point towards eco-effectiveness, socio-effectiveness, sufficiency, and eco-equity as four criteria that need to be met if sustainable development is to be reached.

Critique of the concept of sustainable development

Deforestation and increased road-building in the Amazon Rainforest are a significant concern because of increased human encroachment upon wilderness areas, increased resource extraction and further threats to biodiversity.

Purpose

Various writers have commented on the population control agenda that seems to underlie the concept of sustainable development. Maria Sophia Aguirre writes:[22]"Sustainable development is a policy approach that has gained quite a lot of popularity in recent years, especially in international circles. By attaching a specific interpretation to sustainability, population control policies have become the overriding approach to development, thus becoming the primary tool used to “promote” economic development in developing countries and to protect the environment."Mary Jo Anderson suggests that the real purpose of sustainable development is to contain and limit economic development in developing countries, and in so doing control population growth.[23] It is suggested that this is the reason the main focus of most programs is still on low-income agriculture. Joan Veon, a businesswoman and international reporter, who covered 64 global meetings on sustainable development posits that:[24]

"Sustainable development has continued to evolve as that of protecting the world's resources while its true agenda is to control the world's resources. It should be noted that Agenda 21 sets up the global infrastructure needed to manage, count, and control all of the world's assets."

Consequences

The retreat of Aletsch Glacier in the Swiss Alps (situation in 1979, 1991 and 2002), due to global warming.

Vagueness of the term

A sewage treatment plant that uses environmentally friendly solar energy, located at Santuari de Lluc monastery.

Basis

Sylvie Brunel, French geographer and specialist of the Third World, develops in A qui profite le développement durable (Who benefits from sustainable development?) (2008) a critique of the basis of sustainable development, with its binary vision of the world, can be compared to the Christian vision of Good and Evil, a idealized nature where the human being is an animal like the others or even an alien. Nature – as Rousseau thought – is better than the human being. It is a parasite, harmful for the nature. But the human is the one who protects the biodiversity, where normally only the strong survive.[30]Moreover, she thinks that the ideas of sustainable development can hide a will to protectionism from the developed country to impede the development of the other countries. For Sylvie Brunel, the sustainable development serves as a pretext for the protectionism and "I have the feeling about sustainable development that it is perfectly helping out the capitalism".[30]

"De-growth"

The proponents of the de-growth reckon that the term of sustainable development is an oxymoron. According to them, on a planet where 20% of the population consumes 80% of the natural resources, a sustainable development cannot be possible for this 20%: "According to the origin of the concept of sustainable development, a development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, the right term for the developed countries should be a sustainable de-growth".[31]Sustainable development in economics

The Venn diagram of sustainable development shown above has many versions,[32] but was first used by economist Edward Barbier (1987).[33] However, Pearce, Barbier and Markandya (1989)[34] criticized the Venn approach due to the intractability of operationalizing separate indices of economic, environmental, and social sustainability and somehow combining them. They also noted that the Venn approach was inconsistent with the Brundtland Commission Report, which emphasized the interlinkages between economic development, environmental degradation, and population pressure instead of three objectives. Economists have since focused on viewing the economy and the environment as a single interlinked system with a unified valuation methodology (Hamilton 1999[35], Dasgupta 2007[36]). Intergenerational equity can be incorporated into this approach, as has become common in economic valuations of climate change economics (Heal,2009)[37]. Ruling out discrimination against future generations and allowing for the possibility of renewable alternatives to petro-chemicals and other non-renewable resources, efficient policies are compatible with increasing human welfare, eventually reaching a golden-rule steady state (Ayong le Kama, 2001[38] and Endress et al.2005[39]). Thus the three pillars of sustainable development are interlinkages, intergenerational equity, and dynamic efficiency (Stavins, et al. 2003).[40]Arrow et al. (2004)[41] and other economists (e.g. Asheim,1999[42] and Pezzey, 1989[43] and 1997[44]) have advocated a form of the weak criterion for sustainable development – the requirement than the wealth of a society, including human-capital, knowledge-capital and natural-capital (as well as produced capital) not decline over time. Others, including Barbier 2007,[45] continue to contend that strong sustainability – non-depletion of essential forms of natural capital – may be appropriate.

See also

- Applied Sustainability

- Bright green environmentalism

- C. Arden Pope

- Carrying capacity

- Centre for Development and Population Activities

- Civilization

- Clean tech law

- Cleaner Production

- Conservation biology

- Conservation development

- Conservation ethic

- Cultural landscape

- Ecological economics

- Ecologically sustainable development

- Environmental issue

- Green building

- Green Globe

- Hydroelectricity

- Industrial Ecology

- Living Planet Index

- Limits to growth

- Geothermal energy

- Maximum sustainable yield

- Micro-Sustainability

- Natural environment

- Natural landscape

- Nature

- Outline of sustainability

- List of sustainability topics

- Passive solar building design

- Renewable energy

- Residential cluster development

- Solar energy

- Strategic Sustainable Development

- Sustainable forest management

- Sustainable living

- Sustainable yield

- Sustainopreneurship

- World Cities Summit

- Zero carbon city

]

Organizations and research

- 2010 International Year of Biodiversity

- 2010 Biodiversity Indicators Partnership

- Afrique verte

- Agronomy for Sustainable Development

- Appropedia

- Dashboard of Sustainability

- Earth Charter

- Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei

- Greenhouse Development Rights

- Institute for Environment and Sustainability (IES)

- Institute for Trade, Standards and Sustainable Development (ITSSD)

- International Institute for Environment and Development

- International Institute for Sustainable Development

- International Mountain Day - Dec. 11

- International Organization for Sustainable Development

- National Center for Appropriate Technology

- National Strategy for a Sustainable America

- Sovereignty International

- Stakeholder Forum for a Sustainable Future

- Sustainable Tourism CRC

- The Earth Institute

- The Venus Project

- United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development

- World Citi